|

|||

|

|---|

Facts About Germany German History German Recipes |

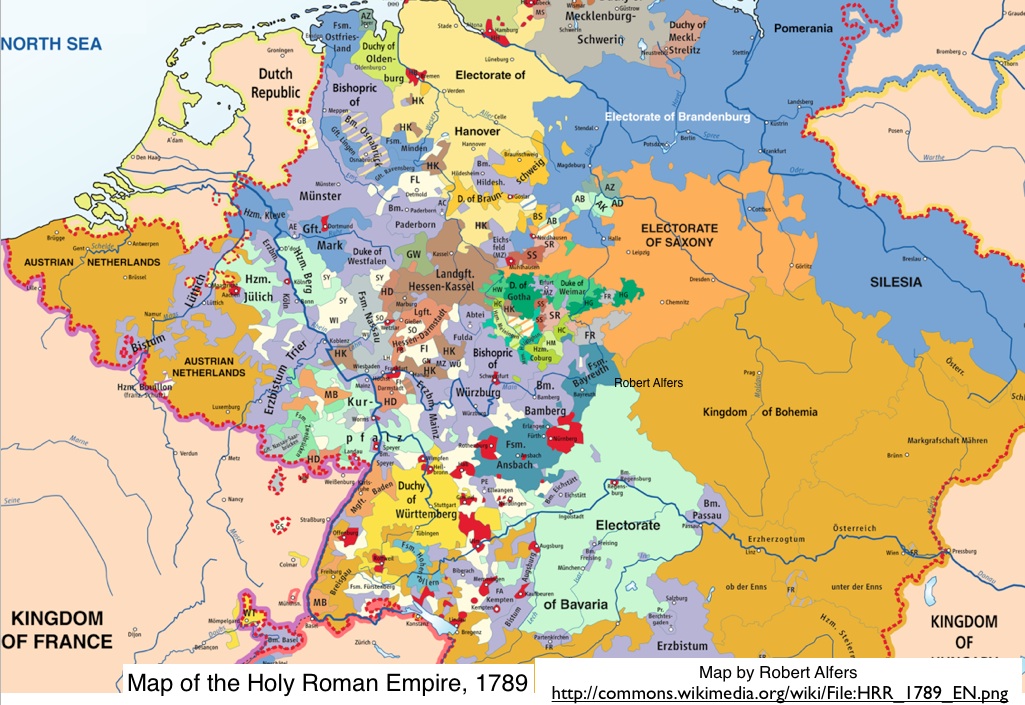

The Smaller States of Germany By the eighteenth century, none of the other states of the German empire were strong enough to have territorial ambitions to match those of Prussia and Austria. Some of the larger states, such as Saxony, Bavaria, and Wuerttemberg, also maintained standing armies, but their smaller size compelled them to seek allies, some from outside the empire. With the exception of the free cities and ecclesiastical states, smaller states, like Austria and Prussia, were governed by a hereditary monarch who ruled either with the consent or help of the nobility and with the help of an increasingly well-trained bureaucracy. Only a few states, such as Wuerttemberg, could boast of an active democracy of the kind evolving in Britain and France. Except in a few free cities, such as Frankfurt am Main and Hamburg, which were active in international trade, Germany's commercial class was neither strong nor self-confident. Farmers in western Germany were largely free; those in the east were often serfs. However, whether in the east or the west, most who worked the land lived at the subsistence level.

Despite its lack of popular democracy, Germany was generally well governed. The state bureaucracies gained in power and expertise, and efficiency and probity were esteemed. During the eighteenth century, the principles of the Enlightenment came to be widely disseminated and applied. Although there were no political challenges to enlightened absolutism, as was the case in France, all phenomena, including religion, were subject to critical, reasoned examination to determine their rationality. In this more tolerant environment, differing religious views could still create social friction, but ways were found for the empire's three main religions--Roman Catholicism, Lutheranism, and Calvinism--to coexist in most states. The expulsion of about 20,000 Protestants from the ecclesiastical state of Salzburg during 1731-32 was viewed by the educated public at the time as a harking back to less enlightened days.

Several new universities were founded, some soon considered among Europe's best. An increasingly literate public made possible a jump in the number of journals and newspapers. At the end of the seventeenth century, most books printed in Germany were in Latin. By the end of the next century, all but 5 percent were in German. The eighteenth century also saw a refinement of the German language and a flowering of German literature with the appearance of such figures as Gotthold Lessing, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, and Friedrich Schiller. German music also reached great heights with the Bach family, George Frederick Handel, Joseph Haydn, and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. - The Age of

Enlightened Absolutism

|

|

|||||||||

Powered by Website design company Alex-Designs.com