|

|||

|

|---|

Facts About Germany German History German Recipes |

Bismarck and the Unification of Germany

Liberal hopes for German unification were not met during the politically turbulent 1848-49 period. A Prussian plan for a smaller union was dropped in late 1850 after Austria threatened Prussia with war. Despite this setback, desire for some kind of German unity, either with or without Austria, grew during the 1850s and 1860s. It was no longer a notion cherished by a few, but had proponents in all social classes. An indication of this wider range of support was the change of mind about German nationalism experienced by an obscure Prussian diplomat, Otto von Bismarck. He had been an adamant opponent of German nationalism in the late 1840s. During the 1850s, however, Bismarck had concluded that Prussia would have to harness German nationalism for its own purposes if it were to thrive. He believed too that Prussia's well-being depended on wresting primacy in Germany from its traditional enemy, Austria.

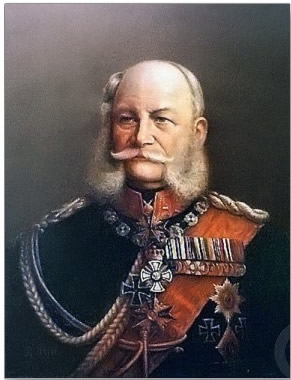

In 1862 King Wilhelm I of Prussia (r. 1858-88) chose Bismarck to serve as his minister president. Descended from the Junker, Prussia's aristocratic landowning class, Bismarck hated parliamentary democracy and championed the dominance of the monarchy and aristocracy. However, gifted at judging political forces and sizing up a situation, Bismarck contended that conservatives would have to come to terms with other social groups if they were to continue to direct Prussian affairs. The king had summoned Bismarck to direct Prussia's government in the face of the Prussian parliament's refusal to pass a budget because it disagreed with army reforms desired by the king and his military advisers. Although he could not secure parliament's consent to the government's budget, Bismarck was a tactician skilled and ruthless enough to govern without parliament's consent from 1862 to 1866.

As an ardent and aggressive Prussian nationalist, Bismarck had long been an opponent of Austria because both states sought primacy within the same area--Germany. Austria had been weakened by reverses abroad, including the loss of territory in Italy, and by the 1860s, because of clumsy diplomacy, had no foreign allies outside Germany. Bismarck used a diplomatic dispute to provoke Austria to declare war on Prussia in 1866. Against expectations, Prussia quickly won the Seven Weeks' War (also known as the Austro-Prussian War) against Austria and its south German allies. Bismarck imposed a lenient peace on Austria because he recognized that Prussia might later need the Austrians as allies. But he dealt harshly with the other German states that had resisted Prussia and expanded Prussian territory by annexing Hanover, Schleswig-Holstein, some smaller states, and the city of Frankfurt. The German Confederation was replaced by the North German Confederation and was furnished with both a constitution and a parliament. Austria was excluded from Germany. South German states outside the confederation--Baden, Wuerttemberg, and Bavaria--were tied to Prussia by military alliances.

Bismarck's military and political successes were remarkable, but the first had been achieved at considerable risk, and the second were by no means complete. Luck had played a part in the decisive victory at the Battle of Koeniggraetz (Hradec Kralóve in the present-day Czech Republic); otherwise, the war might have lasted much longer than it did. None of the larger German states had supported either Prussia's war or the formation of the North German Confederation led by Prussia. The states that formed what is often called the Third Germany, that is, Germany exclusive of Austria and Prussia, did not desire to come under the control of either of those states. None of them wished to be pulled into a war that showed little likelihood of benefiting any of them. In the Seven Weeks' War, the support they gave Austria had been lukewarm.

In 1870 Bismarck engineered another war, this time against France. The conflict would become known to history as the Franco-Prussian War. Nationalistic fervor was ignited by the promised annexation of Lorraine and Alsace, which had belonged to the Holy Roman Empire and had been seized by France in the seventeenth century. With this goal in sight, the south German states eagerly joined in the war against the country that had come to be seen as Germany's traditional enemy. Bismarck's major war aim--the voluntary entry of the south German states into a constitutional German nation-state--occurred during the patriotic frenzy generated by stunning military victories against French forces in the fall of 1870. Months before a peace treaty was signed with France in May 1871, a united Germany was established as the German Empire, and the Prussian king, Wilhelm I, was crowned its emperor in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles.

|

|

|||||||||

Powered by Website design company Alex-Designs.com