|

|||

|

|---|

Facts About Germany German History German Recipes |

Medieval Germany -- The Empire Under the Early Habsburgs

The Great Interregnum ended in 1273 with the election of Rudolf of Habsburg as king-emperor. After the interregnum period, Germany's emperors came from three powerful dynastic houses: Luxemburg (in Bohemia), Wittelsbach (in Bavaria), and Habsburg (in Austria). These families alternated on the imperial throne until the crown returned in the mid-fifteenth century to the Habsburgs, who retained it with only one short break until the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806.

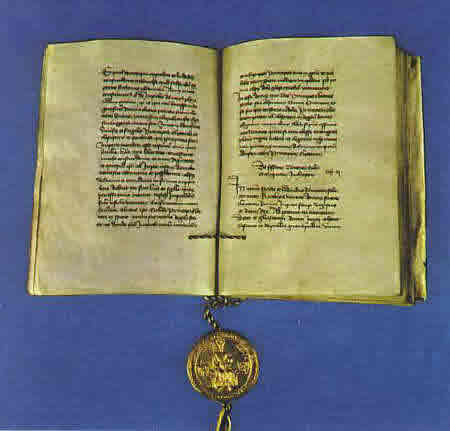

The Golden Bull of 1356, an edict promulgated by Emperor Charles IV (r. 1355-78) of the Luxemburg family, provided the basic constitution of the empire up to its dissolution. It formalized the practice of having seven electors--the archbishops of the cities of Trier, Cologne, and Mainz, and the rulers of the Palatinate, Saxony, Brandenburg, and Bohemia--choose the emperor, and it represented a further political consolidation of the principalities. The Golden Bull ended the long-standing attempt of various emperors to unite Germany under a hereditary monarchy. Henceforth, the emperor shared power with other great nobles like himself and was regarded as merely the first among equals. Without the cooperation of the other princes, he could not rule.

The princes were not absolute rulers either. They had made so many concessions to other secular and ecclesiastical powers in their struggle against the emperor that many smaller principalities, ecclesiastical states, and towns had retained a degree of independence. Some of the smaller noble holdings were so poor that they had to resort to outright extortion of travelers and merchants to sustain themselves, with the result that journeying through Germany could be perilous in the late Middle Ages. All of Germany was under the nominal control of the emperor, but because his power was so weak or uncertain, local authorities had to maintain order--yet another indication of Germany's political fragmentation. Despite the lack of a strong central authority, Germany prospered during the 14th and 15th centuries. Its population increased from about 14 million in 1300 to about 16 million in 1500, even though the Black Death killed as much as one-third of the population in the mid-fourteenth century. Located in the center of Europe, Germany was active in international trade. Rivers flowing to the north and the east and the Alpine passes made Germany a natural conduit conveying goods from the Mediterranean to northern Europe. Germany became a noted manufacturing center. Trade and manufacturing led to the growth of towns, and in 1500 an estimated 10 percent of the population lived in urban areas. Many towns became wealthy and were governed by a sophisticated and self-confident merchant oligarchy. Dozens of towns in northern Germany joined together to form the Hanseatic League, a trading federation that managed shipping and trade on the Baltic and in many inland areas, even into Bohemia and Hungary. The Hanseatic League had commercial offices in such widely dispersed towns as London, Bergen (in present-day Norway), and Novgorod (in present-day Russia). The league was at one time so powerful that it successfully waged war against the king of Denmark. In southern Germany, towns banded together on occasion to protect their interests against encroachments by either imperial or local powers. Although these urban confederations were not always strong enough to defeat their opponents, they sometimes succeeded in helping their members to avoid complete subjugation. In what was eventually to become Switzerland, one confederation of towns had sufficient military might to win virtual independence from the Holy Roman Empire in 1499.

The Knights of the Teutonic Order continued their settlement of the east until their dissolution early in the sixteenth century, in spite of a serious defeat at the hands of the Poles at the Battle of Tannenberg in 1410. The lands that came under the control of this monastic military, whose members were pledged to chastity and to the conquest and conversion of heathens, included territory that one day would become eastern Prussia and would be inhabited by Germans until 1945. German settlement in areas south of the territories controlled by the Knights of the Teutonic Order also continued, but generally at the behest of eastern rulers who valued the skills of German peasant-farmers. These new settlers were part of a long process of peaceful German immigration to the east that lasted for centuries, with Germans moving into all of eastern Europe and even deep into Russia. Intellectual growth accompanied German expansion. Several universities were founded, and Germany came into increased contact with the humanists active elsewhere in Europe. The invention of movable type in the middle of the fifteenth century in Germany also contributed to a more lively intellectual climate. Religious ferment was common, most notably the heretical movement engendered by the teachings of Jan Hus (ca. 1372-1415) in Bohemia. Hus eventually was executed, but the dissatisfaction he felt toward the established church was shared by many others throughout German-speaking lands, as could be seen in the frequent occurrences of popular, mystical religious revivalism after his death. - The Merovingian Dynasty,

ca. 500-751

|

|

|||||||||

Powered by Website design company Alex-Designs.com